On Magical Writing and a Gypsy Named Kerouac

There’s this thing that writers have, this belief that if you talk about the magic, it disappears. Dries up. That we’ll jinx ourselves. Of course I’m talking about the writing process. And of course, all of the above superstition is bullshit.

I’m a firm believer in knowing how things work — in the deconstructing and unpacking and boiling it down to a few key elements. But there aren’t any guarantees. Variables change. The process does not remain the same. But there are some pretty interesting things to learn from examining how (and even why) we write, especially if we operate under the assumption that if we know how we did something, we can duplicate it. Or try to.

Perhaps I’m so obsessed with process because sometimes writing feels like a fluke — like it was an accident, and now I’ve got to figure out how I got from Point A to Point B to prove to myself that I actually did it. So how do we do it? Good question. I don’t have the answer, but I know it’s different for everyone.

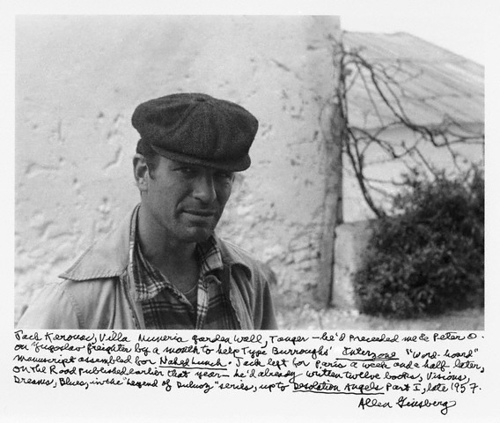

Once, when I was an angsty, moody teenager, I believed that writing should only happen when the mood is right. When the muse strikes. Which is pretty damn funny when you think about it, because if anyone operated solely on the muse, no one would get anything done. But let’s hold off on that and get back to teenage me. Teenage me was also overly self-impressed that I had read Kerouac’s “On the Road” in high school, so with my rudimentary research skills, it might make sense how a.) I had come to the conclusion that Kerouac didn’t revise his work and b.) that I, too, could be like Kerouac. Ah, the fallacy of youth.

Once, when I was an angsty, moody teenager, I believed that writing should only happen when the mood is right. When the muse strikes. Which is pretty damn funny when you think about it, because if anyone operated solely on the muse, no one would get anything done. But let’s hold off on that and get back to teenage me. Teenage me was also overly self-impressed that I had read Kerouac’s “On the Road” in high school, so with my rudimentary research skills, it might make sense how a.) I had come to the conclusion that Kerouac didn’t revise his work and b.) that I, too, could be like Kerouac. Ah, the fallacy of youth.

It is rather romantic, though, to imagine that he typed up a highway epic — a raging love letter of sorts — on a 120-foot roll of taped together teletype in three weeks and finished with the perfect, pristine product rolled up all neat and sparkling on his desk. But let’s be honest: Kerouac had planned for that book, and big time. He didn’t just sit at a typewriter all hopped up on Benzedrine and juice and go nuts. He had a process. He (and pretty much every writer in history) had a penchant for small notebooks, in which he’d record copious notes and sections of early drafts. Here’s the brief timeline: The first versions of the novel emerged in 1948. “The Scroll” itself was typed up in 1951. Revisions occurred from 1951 to 1957, and the novel was published in 1957.

I guess my point is that even the most “spontaneous prose” is planned. From the initial germ of idea (which in this case was a letter from Kerouac to fellow compatriot and all-around buddy Neal Cassady, detailing his adventures) to the finished thing, there’s a way to get there. A how to get there. Understanding the how would benefit writerly success on any level. While it’s magical to imagine that writers write best when the muse strikes, we’ve got to remember that every magician has a trick. For writers, that starts with the process.

Nice insight. I too am obsessed with process. I like that you openly admit to being a deconstructionist. One of my favorite sites is How a Poem Happens (http://howapoemhappens.blogspot.com/) from Brian Brodeur. Brodeur features a poem, then asks the poet a series of questions on how the poem came about, how was it edited and so forth. It’s all about this issue.

Good article!

Grace, that’s a great website. I was browsing through and it’s chock full of really great stuff. It’s interesting to see the differences and similarities between the processes across genre. For example, would you see a big difference between the way a writer creates a poem vs. an essay? What would that look like? It’s pretty rich territory and might warrant some exploration.

The other thing I struggle with when I write about process (mine or someone else’s) is how to present it in an interesting way. I think the interview style is great, but are there other formats to present it, as well? I’m just thinking of ways to interrogate and pick apart process beyond your traditional essay or interview style. Suggestions? Anyone?